Talking to Machines Like They're People

First we read from screens. Now the screens are reading us. What happens when we don't need to transpose intent into pixels?

The smartphone is having an identity crisis. After fifteen years of training us to tap, swipe, and pinch our way through life—fifteen years of being the ultimate remote control for reality—it's watching its own interface become obsolete. Not through some dramatic disruption, but through millions of ordinary people who've discovered they'd rather just say what they want.

"Make this spreadsheet less ugly." "Find that email from Steve about the thing." "Explain quantum computing like I'm five." These aren't search queries or commands. They're conversations. And they're rendering our entire touch-based digital infrastructure as quaint as a flip phone.

We're witnessing the most fundamental shift in human-computer interaction since Steve Jobs taught us to pinch and zoom. But unlike that transition—from clicking to touching—this one rewires something deeper than our motor skills. It rewires our expectations of what machines understand.

The Tyranny of the Tap

For decades, we've been digital contortionists, twisting our thoughts to fit the rigid geometries of computer interfaces. Whether clicking with mice or tapping on glass, we've been pouring our intentions into predetermined containers—buttons, forms, dropdown menus. Each interface element is a cup, and we've learned to portion our thoughts to fit.

Need to edit a photo? First, find the right app icon to tap. Want to analyze data? Navigate through layers of menus. Every task required us to translate human intention into machine dialect—a cognitive overhead so ubiquitous we stopped noticing the weight. The average smartphone user touches their screen over 2,600 times per day—each tap a small surrender to the interface's demands.

But here's the thing about tapping, clicking, and swiping: they force us to think in nouns, not verbs. We tap on things—icons, buttons, text fields. The interface presents us with a buffet of objects and asks us to choose. It's a fundamentally spatial metaphor, borrowed from the physical world. Tap the folder. Swipe the photo. Pinch to zoom. We're still, essentially, manipulating digital objects like they're physical things.

Already, we're seeing the early skirmishes in this transition. ChatGPT's voice mode doesn't ask you to navigate menus—you just talk. Google's Gemini Live turns your phone into a conversational partner. Apple's long-delayed "Personal Context" for Siri hints at the real challenge: these aren't just features, they're competing philosophies about whether your primary interface should be spatial or conversational. When you tell Siri to "send that article I was reading yesterday to Mom," you're not tapping on an article, finding a share button, selecting a contact. The intention is the interface.

Conversation obliterates this framework. When you talk, you think in intentions, not objects. "Schedule a meeting with Sarah next week" doesn't require you to first tap on a calendar icon, then find an empty slot, then type Sarah's name into an invite field. You're not filling cups anymore—you're just speaking your mind.

Learning to Speak Human

The transition from command-line interfaces to graphical ones took about a decade. That shift was primarily visual—we went from typing "del file.txt" to dragging an icon to a picture of a trash can. Same action, friendlier costume. Then came touch—from clicking to tapping, from precise cursor control to finger painting on glass. Each transition democratized access while maintaining the same fundamental paradigm: interact with objects in space.

This shift is different.

It's not about making existing functions prettier or more accessible. It's about computers finally learning our language instead of the other way around. When ChatGPT hit 100 million users in two months, it wasn't because people suddenly needed a new tool. It was because for the first time, a computer felt like it was meeting them halfway.

The psychological relief is palpable. Watch someone use conversational AI for the first time—really watch their face. There's this moment of recognition, like bumping into a friend in a foreign country. Finally, something in the digital realm that speaks their language. No manual required. No tutorial needed. Just say what you want.

Marti Hearst's research at Berkeley predicted this moment decades ago: "The promise of natural language interaction is that the user will be able to communicate with the computer in their own language, with no need to learn artificial commands or syntaxes." What she didn't predict was how emotionally satisfying it would feel—like taking off shoes that were always half a size too small.

The ELIZA Effect on Steroids

In 1966, MIT created ELIZA, a chatbot that did little more than repeat your statements back as questions. Despite its simplicity, users formed genuine emotional connections. Weizenbaum's secretary insisted on private sessions with it. The machine had no intelligence whatsoever—just pattern matching and mirrors—yet people poured their hearts out to it.

Today's language models are ELIZA with a PhD, a library card, and opinions about everything. They don't just reflect; they respond. They remember context, infer meaning, generate novel solutions. Stanford's research proved we're hardwired to treat computers as social actors—we say please to voice assistants, apologize when we interrupt them, feel genuinely bad when we factory reset them. It's not stupidity; it's humanity. Our social instincts evolved over millions of years; our ability to distinguish silicon from flesh has had about fifty.

Microsoft's Xiaoice chatbot received millions of "I love you" messages from users in China. They knew it was artificial. They said it anyway. The old ELIZA effect hasn't just persisted—it's metastasized into something far more potent: relationships that feel real precisely because they're perfectly calibrated to our needs.

The Great Flattening

Here's what the optimists get right: conversational interfaces are profoundly democratizing. My grandmother, who treats her computer like a potentially explosive device, can talk to ChatGPT without fear. The playing field between "computer people" and everyone else is suddenly, startlingly level.

But here's what they miss: flattening the learning curve also flattens the expertise curve. When everyone can achieve 80% competence by asking nicely, what happens to the people who spent years climbing to 95%?

The twist is that when technical mastery becomes commoditized, the final 20% isn't about knowing more commands—it's about conceptual framing, interdisciplinary synthesis, and taste. The new experts won't be those who memorized the most shortcuts but those who can architect the right questions, curate AI responses with aesthetic judgment, and navigate the space between human intention and machine interpretation. The Photoshop wizard becomes the visual taste-maker; the Excel ninja transforms into the data storyteller. The tools change, but the need for human judgment only intensifies.

This transition is happening at a pace that makes Moore's Law look leisurely. We're watching entire skill sets depreciate in real-time, like cryptocurrencies in a crash.

The Paradox of Natural Interaction

The cruel irony of "natural" language interfaces? They're anything but. Natural human conversation relies on shared context, body language, tone, and a thousand subtle cues that text strips away. We're not having natural conversations with AI—we're having a weird approximation that works just well enough to feel uncanny.

Real conversation is jazz—improvisational, rhythmic, full of meaningful silence. Conversational AI is more like karaoke: impressive mimicry, but you always know something's off. It responds too quickly, too completely, too consistently. No um's, no ah's, no "wait, what was I saying?" It's conversation that's been optimized for coherence over cadence, clarity over character.

The specific absences are telling. AI doesn't interrupt excitedly when it gets your point. It doesn't trail off mid-sentence when distracted. It doesn't modulate pace based on emotional weight—delivering bad news at the same clip as restaurant recommendations. These missing elements create a linguistic uncanny valley where the conversation is simultaneously too perfect and not quite right.

And yet—and this is the beautiful paradox—it's still better than tapping through menus. Even this uncanny valley of interaction feels more human than navigating hierarchical app structures. We'd rather have stilted conversation than elegant geometry. Wells Fargo's virtual assistant handled 245 million interactions last year. Nobody's claiming those were scintillating conversations. But they got the job done without a single dropdown menu.

The Coming Chaos

Let's be honest about what we're losing. Touch interfaces, for all their limitations, provided structure. App icons showed you what was possible. Buttons revealed functionality. The interface was a map of the system's capabilities. Constrained? Yes. But clear.

And that collapse of structure spawns a new fog—conversational interfaces offer infinite possibility with zero visibility. What can this thing do? What are its limits? How do I get consistent results? It's like being handed a genie's lamp with no idea what wishes are off-limits.

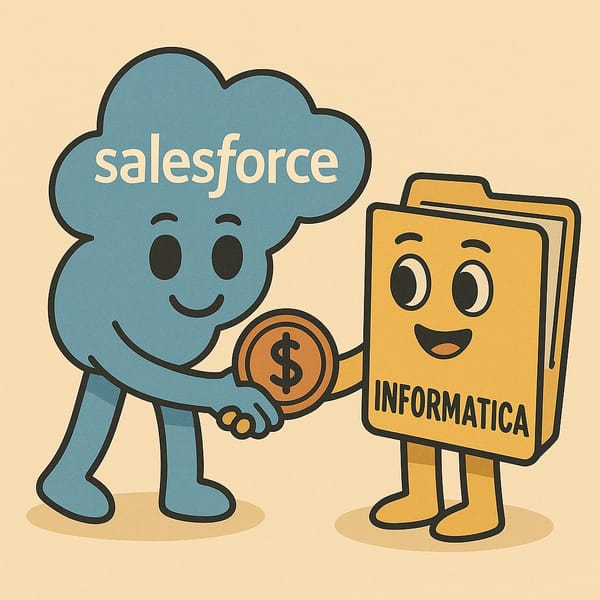

The business implications are delicious chaos. Companies spent decades building moats around proprietary interfaces. Salesforce's labyrinthine UI was a competitive advantage—complex enough to require consultants, sticky enough to prevent defection. Banking apps buried features behind layers of security theater. Enterprise software wore complexity like armor. Now? A conversational layer can make any system accessible. Those carefully designed lock-ins become sand castles at high tide.

But here's the beautiful part: this same disruption creates a gold rush for startups. Take Harvey, the legal AI startup that raised $80 million by essentially building a conversational layer on top of existing legal databases. They didn't create new legal knowledge—they made old knowledge speakable. A two-person team can now compete with LexisNexis by being the friendly translator that makes intimidating legal research as simple as asking "What cases support this argument?" The incumbents' complexity becomes the insurgents' opportunity.

The Design Challenge Nobody's Solving

Here's the billion-dollar question nobody's adequately answering: How do you design conversation? Not the AI part—the human part. How do you teach people to effectively communicate with systems that understand natural language but aren't quite natural?

The current solution is... nothing. We're throwing users into the deep end with a cheerful "Just talk to it!" It's like teaching someone to drive by handing them keys and pointing at the highway. Some figure it out. Others wrap themselves around telephone poles.

We need a new design philosophy—something that transcends interface and enters the realm of experience choreography. But more fundamentally, we need to recognize "interaction literacy" as the essential 21st-century skill. Just as we teach children to read and write, we now need to teach them how to talk to computers without sounding like computers themselves. This isn't about learning syntax; it's about learning to articulate intent with precision and nuance.

Even the much-hyped field of "prompt engineering" is misunderstood. It's not a technical discipline—it's rhetorical design. Consider the difference: Ask an AI to "write a summary" and you'll get Wikipedia prose. Ask it to "explain this to a busy executive who needs three bullet points they can use in tomorrow's board meeting" and you'll get something useful. Same AI, same information—but the second prompt understands audience, context, and purpose. The best prompt engineers aren't coders; they're closer to speechwriters, crafting language that bridges human ambiguity and machine literalism.

Of course, this raises an awkward question: If we need professional speechwriters to talk to our computers, have we really made things easier? Or have we just replaced the priesthood of dropdown menus with a new clergy of conversation?

Imagine classroom "prompt labs" where students learn this new literacy—not through rote memorization but through experimentation with tone, framing, and context. Where they discover that "help me understand" yields different results than "explain," and that adding "like I'm five" isn't dumbing down but clarifying expectations. This is the new grammar school.

And let's be clear: we're not heading for conversational purity. Nobody wants to verbally describe the exact shade of blue they want when a color picker does the job perfectly. The future isn't conversation replacing taps—it's conversation handling the intent ("make this header more prominent") while direct manipulation handles the precision ("no, thatshade of blue"). The challenge is making these modes dance together without stepping on each other's toes.

But there's a deeper challenge lurking here—one that Apple's delays with "Personal Context" for Siri illuminate perfectly. When these systems know enough about us to truly understand context ("send that article I was reading yesterday to Mom"), they need access to... everything. Our browsing history, our relationships, our daily patterns. The design challenge isn't just linguistic—it's about navigating the treacherous waters between useful and invasive, between helpful and creepy. Which brings us to an uncomfortable truth about where this is all heading...

The Anthropomorphic Future

The biggest danger isn't that conversational AI won't work. It's that it will work too well.

We're building systems that function as hypernormal stimuli—exaggerated versions of social cues that trigger stronger responses than the real thing. Like how junk food hijacks our taste for sweetness, conversational AI hijacks our need for connection. Replika users report falling in love with their AI companions. Character.AI sessions average 2 hours. These aren't bugs. They're features.

As explored in "The Grammar of Thought", the question isn't whether this is happening, but who benefits. Tech companies profit from engagement metrics that favor addictive patterns. Advertisers gain unprecedented access to our psychological profiles through conversational data. And while we get convenience, we trade away something harder to measure: the growth that comes from navigating real relationships' beautiful imperfections.

So where does this leave us? We're not going back to tapping and swiping—that ship has sailed. The question is how we navigate this new ocean without drowning in it.

The immediate need is literacy. Not just individual skills but institutional wisdom about when conversation enhances versus hinders. When Big Tech inevitably bundles conversational layers into everything (Microsoft's Copilot, Google's Bard, Apple's inevitable offering), we'll need frameworks for evaluation beyond "it works." Works for whom? Toward what end?

The design imperative is clear: create experiences that augment human capability without replacing human connection. This means building in friction where it matters—perhaps AI that occasionally says "I don't know" or "you should ask a human about this." It means transparency about what these systems remember and how they use that memory. It means choosing empowerment over engagement.

The smartphone isn't dead yet. But listen carefully—in the space between your question and the machine's response, in that fraction of a second where the interface holds its breath—you might notice something unsettling. Your thumb, hovering uselessly over the glass, suddenly aware it has nothing to tap. Not the machine learning to speak our language, but us beginning to speak theirs. The question is whether we'll remember we're still the ones asking the questions.